Bondi, kangaroo, cooee – what do these typically Australian words have in common? They’re all derived from Aboriginal languages. While borrowing from Aboriginal languages is nothing new, the past two decades have brought an increased recognition of the original names of Aussie landmarks, cities and towns. Reinstating the First Nations name of a place, or adopting dual-naming practices, is a way to acknowledge Aboriginal cultural connections and the rich pre-colonial history of Australia.

Did you know? There are more than 250 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander languages in Australia, including around 800 dialects.

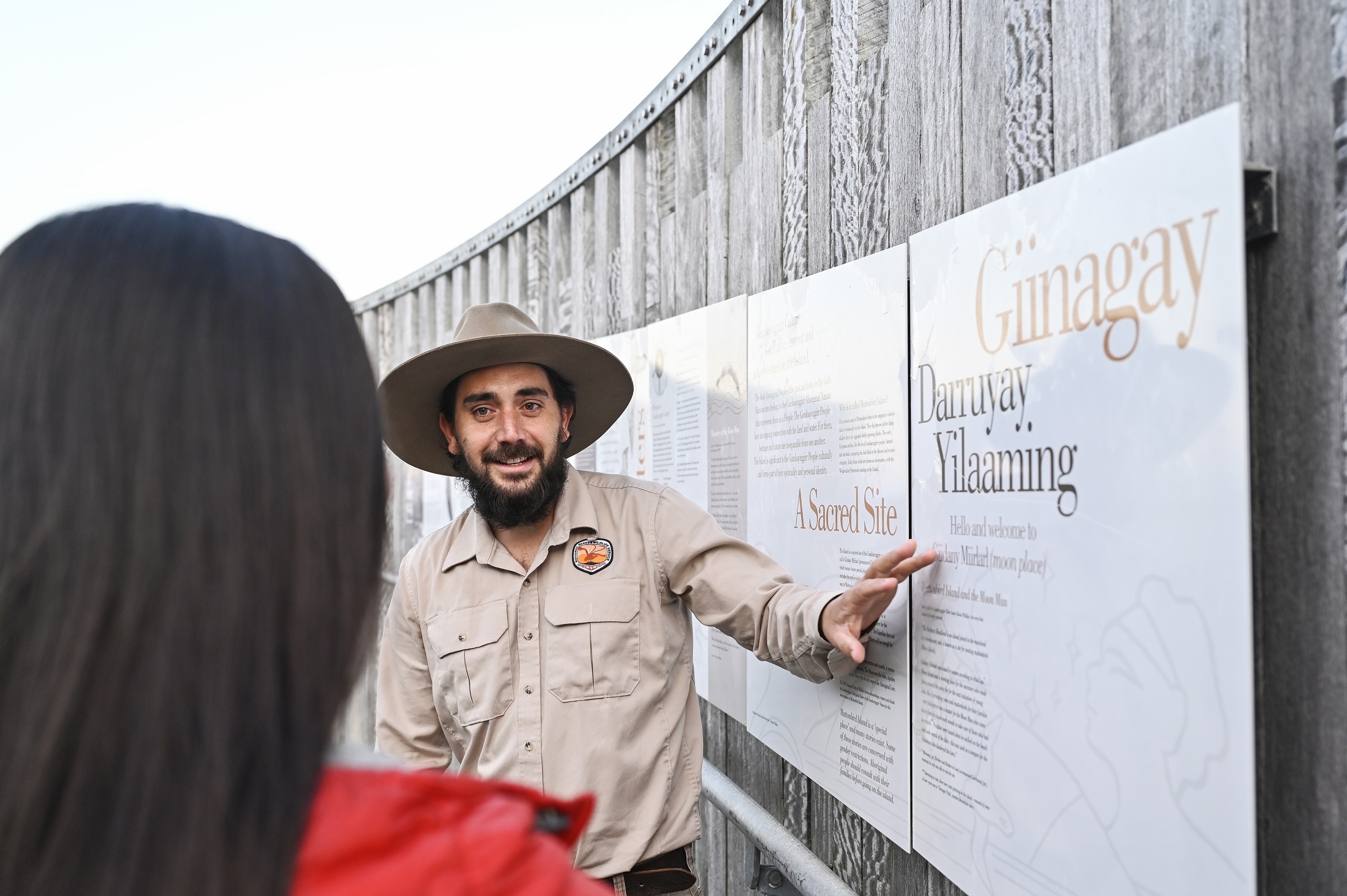

Learn from Aboriginal Discovery rangers on guided tours in national parks.

Muttonbird Island Nature Reserve

Adam Hollingworth/DCCEEW

Back in 1993, Uluru became the first iconic Australian landmark to receive an official dual name in the Northern Territory. Today, it’s exclusively referred to by its Aboriginal name. Most of us also know the name of the Aboriginal Country that we live or work on with Acknowledgements of Country embedding recognition and respect for First Nations people into our everyday speech. These changes are evidence of the power that language holds.

As stewards of over 9.5% of the land in NSW, the National Parks and Wildlife Service has a major role to play in this conversation. From long-standing dual named Aboriginal parks to more recent name changes, we work closely with local traditional owners to ensure our park names reflect, protect and celebrate Aboriginal cultural heritage.

Learn more: Our Park Names Policy says that parks should be named after a prominent natural feature in the landscape and the local Aboriginal name of the feature is preferred.

-

What’s in a name?

Photo Information

Photo InformationAboriginal hand stencil.

Wollemi National Park

Daniel Tran/OEH

Place names carry huge significance – they help us identify what makes a place unique and who the land belongs to. And there’s always a story behind the name. In Australia, many places have been named after colonisers and sadly some carry shameful stories of discrimination.

Did you know? Boundary Street in Brisbane was named after the boundary that separated European settlers from local Jagera and Turrbal people. After public debate over changing the name, it has stayed in place as a reminder of the crimes of the past.

Learning these stories is an important part of truth-telling, a process that “acknowledges the historical silencing of injustices and ongoing impacts of colonisation on First Nations people”. The decision to reinstate a place’s Aboriginal name is a powerful way to reverse this erasure, recognise custodianship of the land and preserve Aboriginal languages.

Photo Information

Photo InformationNigel Stewart is an Aboriginal guide who works on the Dolphin Dreaming education program.

Arakwal National Park

Aristo Risi/DCCEEW

Learn from the locals: Our Aboriginal rangers run guided tours in national parks across the state. Book your unforgettable cultural experience here.

-

Addressing historical injustice: The story of Beowa’s name change

Photo Information

Photo InformationBeowa’s distinctive red rock coastline.

Beowa National Park

Adam Hollingworth/DCCEEW

Renaming of national parks is rare, but the story of Beowa National Park (formerly Ben Boyd National Park) is a perfect example of when this might happen. Located on the NSW Far South Coast, the park was renamed in November 2022 following extensive consultation with the Aboriginal and South Sea Islander community.

Did you know? Beowa means ‘orca’ or ‘killer whale’ in the local Thaua language. Orcas hold historic, spiritual and cultural significance for Aboriginal groups from this area, playing a key role in cultural practices related to the ocean.

Photo Information

Photo InformationA local resident.

Beowa National Park

Rachelle Mackintosh

Aboriginal community leaders had been calling for the change for several years due to Ben Boyd’s involvement in ‘blackbirding’ – a slavery practice that saw Boyd remove Indigenous people from the islands of Vanuatu and New Caledonia to work on his properties. Changing the park’s name is a way to acknowledge this history and formally recognise the spiritual lives and cultural identity of the area’s first inhabitants.

“It rectified wrongs of the past by taking the honour away from someone that didn’t deserve it and acknowledges Aboriginal people,” BJ Cruse, Chairperson of the Eden Local Aboriginal Land Council, said at an event celebrating the name change.

More on the consultation process to rename the park here.

DownloadNSW National Parks appDownload your next adventure -

Recognising cultural significance: Dual naming of parks and locations

Photo Information

Photo InformationLearn about local Aboriginal culture at Birubi Point Aboriginal Place.

Tomaree Coastal Walk

Tomaree National Park

Remy Brand/DCCEEW

Declared in 1894, Ku-ring-gai Chase is one of the oldest national parks in Australia. Its name combines an Aboriginal word for hunting ground (ku-ring-gai) with its rough English translation (a chase is an area of land reserved for hunting). In recent years, this dual naming approach has been adopted at a range of locations across the state as a way to recognise the continuing cultural connections of local Aboriginal people.

Photo InformationThree large bronze sculptures of significance to the Gweagal Aboriginal People were installed along the Burrawang walk in 2020 to acknowledge the 250th anniversary of the encounter between Aboriginal Australians and the crew the HMB Endeavour in 1770.

Whales bronze sculpture, Burrawang Walk

Kamay Botany Bay National Park

Lisa Sturis/DCCEEW (2020)

Photo InformationThe Canoes bronze sculpture, Burrawang Walk

Kamay Botany Bay National Park

Katherine Ashley/DCCEEW (2020)

Photo InformationOne of the 3 bronze sculptures of significance to the Gweagal Aboriginal People

The Eyes of the Land and the Sea bronze sculpture, Burrawang Walk,

Kamay Botany Bay National Park

Katherine Ashley/DCCEEW (2020)

Some of the parks and locations that have adopted dual names include Kamay Botany Bay National Park, Barunguba Montague Island Nature Reserve and, most recently, the Byron Bay landmarks of Nguthungulli/Julian Rocks and Walgun/Cape Byron. From significant historical events to sacred Aboriginal sites and important gathering places, these areas hold special significance for First Nations people. Their dual names invite visitors to learn about this fascinating layered history.

Did you know? Many of our parks are managed in collaboration with Aboriginal owners. Find out more about the joint management of parks here.

Me-Mel (also known as Goat Island), in Sydney Harbour National Park, is in the process of being transferred to Aboriginal ownership. In the future, this culturally significant island will we owned, governed and managed by Aboriginal people. Learn more about this project.

Next time you pay a visit to one of our parks, keep an eye out for signage with Aboriginal place names and find out the meaning behind them. It’s a small way to appreciate the world’s oldest continuing living culture, whose people have helped preserve this land for hundreds of thousands of years so that you can enjoy it today.

Burrawang Walk

Kamay Botany Bay National Park

Natasha Webb/DCCEEW

Stay safe in national parks by checking park alerts for closed parks and safety information, planning for the weather conditions and following our bushwalking safety tips if you’re heading out on a hike.